By Joan F. Peters, Esq., Executive Director

National Aphasia Association

When I tell people I work for the National Aphasia Association, I usually get a blank look. Then, when I describe the condition, over and over again I hear, “Oh my father had that. He couldn’t talk after his stroke. I didn’t know that’s what it was called.”

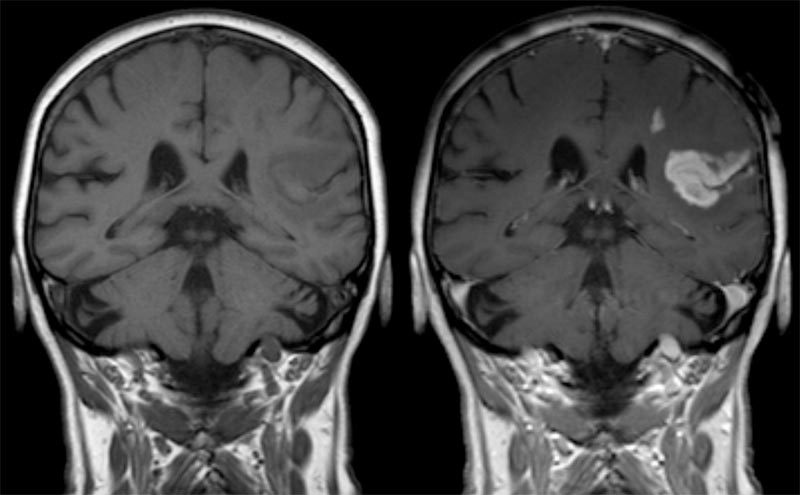

Aphasia is a condition that usually results from stroke or other brain injury. It damages parts of the brain involved with communication. People with aphasia have trouble expressing themselves and/or understanding what others are saying to them. Many people with aphasia also have trouble with reading and writing. But, their thought process is the same as it was before. It is as if there is a short circuit in the brain between the ability to think and the ability to use language; people with aphasia are literally trapped inside their own heads. Because they have a hard time making their needs known, they can become frustrated, isolated and depressed. Aphasia affects about 25-40% of stroke survivors, or more than 1 million Americans

It cannot be cured, and there is no pill yet to make it better. Working with a speech-language pathologist is often effective, but insurance and Medicare coverage for speech therapy is becoming increasingly limited. To make matters worse, even though aphasia is relatively common, many people with aphasia are discharged from the hospital with little information about how to live with it. (One study found that a significant percentage of spouses of people with aphasia lacked a basic understanding of the condition.)

Yet there are simple steps that spouses, caregivers, friends and relatives can take to further communication and make the condition less devastating:

- Many people with aphasia say their aphasia gets worse when they are in a stressful or pressured situation. Give the person with aphasia time to finish his/her sentences. Even if you think you know what they are going to say, wait until you get a clear signal that your suggestion would be welcome.

- Be sensitive to background noise and turn off radios, TVs, appliances. Keep your voice at a normal level as shouting will not help. Group conversations and family dinners can be difficult for people with aphasia.

- Try using pictures, gestures, writing, and facial expressions. The important thing is to get the point across, not that one’s speech be perfect.

- Use yes/no questions to check that the person with aphasia has understood you. (But make sure they are using “yes” and “no” appropriately; some people with aphasia will say “no” when they mean “yes,” especially right after their stroke).

The National Aphasia Association (NAA) provides information for people with aphasia, caregivers and others on its website www.aphasia.org; or you can call toll-free (800) 922-4622 to order information packets. The NAA also publishes The Aphasia Handbook: A Guide for Stroke and Brain Injury Survivors and Their Families. The neurologist and author Oliver Sacks, MD, calls the Handbook, “an essential resource for people with aphasia and their families.”